The everyday inventiveness of translocal relationship maintenance

I’m excited to share some early insights from our latest study. Some of you may remember it from when it was distributed: a survey about how people who sustain relationships online create a sense of being in the same place, even at a distance.

Even now, online platforms are marching towards a future of standardised, formless, and profoundly placeless design. But relationships need place (Tuan, 1979), and people will continue to fashion new tactics to address their everyday needs. So, how do people in translocal relationships play with/around these technological limitations? How do they foster shared places on platforms that aren’t designed for it?

That’s what our study sought to uncover, and here’s what we found…

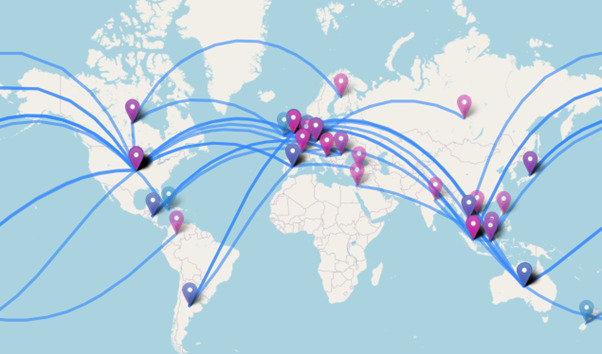

Our deepest thanks to all who participated in the survey! We had 44 respondents—almost twice as many as we were hoping for—and more importantly, we got a pretty broad slice of translocal connections across the world:

Our original focus was on long-distance families and romantic relationships, mainly because people conventionally assume physical closeness and cohabitation in those relationships. But in practice, the data we gathered contained accounts of all kinds of relationships, so we expect the findings to be relevant (in varying degrees) to many kinds of online connection as well.

Across the data, a few themes showed up repeatedly, and through an extensive process of coding and clustering, we’ve distilled it into five themes, or key drivers of practices in virtual placemaking:

1. Synchronicity ⌚

People seek to act in concert and in temporal proximity, to feel a sense of relatedness—be that by experiencing media together, collaborating on a project, or just feeling collocated via a background voice call. Voice calls often scaffolded these kinds of synchronous activities—sound is a great vector for conveying simultaneity/”at the same time.”

2. Persistence 📌

We talked about synchronous interactions above. Asynchronous interactions, on the other hand, assert the “being in the same space.” This requires virtual spaces to not simply disappear or refresh when the session is closed: you’re able to leave artefacts for others to discover even when you’re offline or “in the background,” and they accumulate over time. That’s a core trait of a real place (as discussed in past research).

3. Emotional connection/depth 🫂

We know from other research that long-distance couples favour text messaging. Verbal communication is paramount in relationship deepening because it supports precise expressions of care and affirmation. But it can be asserted by other expressions too, like offers of help, favours and gifts—implicitly or explicitly indicating that one has the other person in one’s thoughts, as well as their interests, well-being, and goings-on.

4. Physical linkage 🔗

Despite the focus on virtual spaces, many respondents saw great importance in anchoring their bonds in physical space, and used technologies as windows, or bridges, linking those spaces together. Using video calls as “windows” to have meals together, virtual house tours where the smartphone acts as a surrogate for the person on the other end, buying the same game board and playing against each other by replicating each other’s moves…our data was replete with creative ways of bridging physical divides.

5. Co-creation 🖼️📝

Collaborative narratives and creation uniquely allow for interactors to explore and cohabit a shared mental place, in which they have an equal stake and are emotionally engaged. It’s a way of being psychically co-present through roleplay and active imagination. Our data was full of mentions of collaborative creative work and narratives, from Dungeons and Dragons to building worlds together to making art of imagined alternate realities.

Other neat insights:

- Rather than ever being confined to a single platform, almost everyone inhabited and interwove practices across different platforms/media types, each with its own utility, affect, and meaning: this is what Madianou calls “polymedia life.” Think playing games on a virtual board while discussing it in a text chat, watching a show together on a streaming website while discussing it in a call, playing Wordle independently and checking in with the group chat to see what others thought, etc. This was almost universal across the dataset!

- There were a lot of unique practices described in the dataset (i.e. instances where one respondent was the only person in the dataset who did that thing) – and yet it was never described as a practice we deliberately designed to solve a problem. This everyday inventiveness among people in translocal/transnational relationships has become the core of our research interest.

- Lots of intergenerational connection (parent/child, grandparent/grandchild, aunt/uncle/niece) was evidenced – and a strong skew towards text chat, video calls, and voice calls for these. Video games are far more common among romantic relationships.

That’s all for this post—I’ll be back soon (very soon) to talk about what comes next.

Leave a Reply