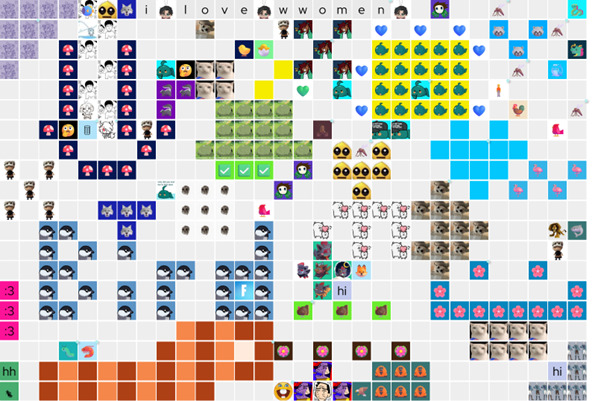

The first room in Experiment 2.

I’ve always been fascinated with apps that convey a sense of things happening “in the same place.” From Minecraft servers to shared Google documents, many virtual platforms seem to foster a sense of shared geography by virtue of their design.

Ever since the research survey, I feel like I’m approaching a sense of what makes a virtual platform feel like a place, and the most succinct way to state those insights thus far is that it’s a combination of:

- Real-time

- Persistence

- Pictures, and

- Words.

To break this down a little: the platform should support a back and forth of interactions between users who are present at the same time. This makes up what some refer to as co-presence (Schroeder, 2002). It should also support scattered, accumulative interactions between users who are not present at the same time. Changes made by one person should alter the app’s state for everyone else, but also remain in place for subsequent users to see and engage with.

As for what media actually gets sent/placed in an app like this, this varies massively across platforms with different aims, but for something to feel like a place, it seems that the minimum is a combination of both spatial (i.e. visual or positional) and precise (textual) communication. (While media types aren’t the focus of this post, it’s a curious hunch that I will explore later.)

All of these traits would ideally be woven together into a single continuous interaction experience (rather than separate texting, drawing and streaming features, for example). The user does the rest of the work: the feeling of place emerges from what they do with the platform.

And it largely cannot be forced. But when it happens, it can be exciting!

—

So, let’s start designing a place-like app from first principles!

It’s easy to take for granted all the design elements needed to project an app’s capabilities. People don’t automatically “buy into” the synchronicity and asynchronicity of an app: it must be built to telegraph these features. They must be made aware that:

- There are others are “present” on the same platform,

- Their actions are being broadcast to all concurrent users as they happen, and,

- Their changes won’t simply vanish after the browser is closed.

#3 seems complex to telegraph, but it is actually the easiest solved. New users should be introduced to the app via an instance (document, room, world, whatever) that is not blank. Ideally, it would already been altered in deliberate ways.

Oftentimes, having something already there is simply the natural result of a user bringing a friend into the experience, but if you’re the one launching it, you might want to put something clearly hand-made in the very first instance you publish, an exemplar to “seed” the possibilities of the app. Approach it playfully.

Now for the pricklier part. We would like our place-like app to feel synchronous, so it should update in real time. What are some ways to do this?

While I don’t want to bring too much jargon into this, we can’t really discuss this in abstract without at least touching on what technologies are available to us.

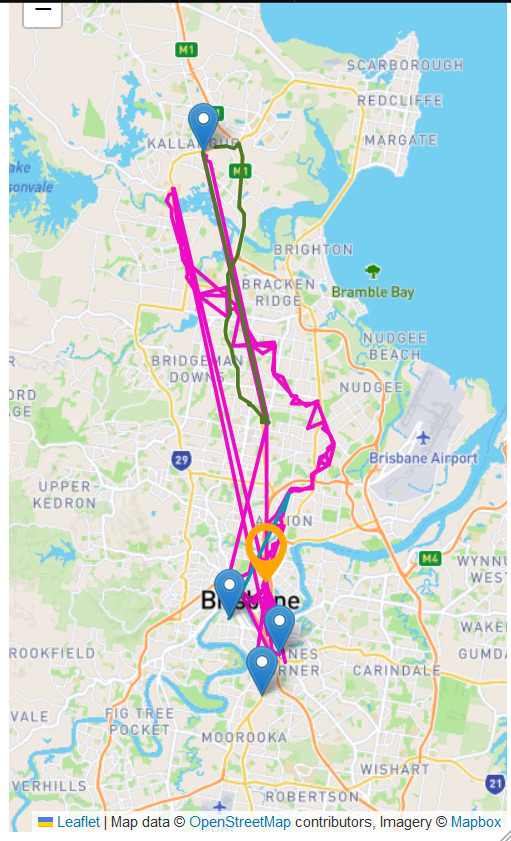

Before the PhD, all my synchronous apps worked by polling a server. For lightweight apps without much of a userbase, it does the job. It’s how my first PhD related web project, Two Map, works, actually. An app that tacitly plots movement on a map, it sends your location data back to a server and retrieves any updates since the last call.

(My supervisor called this a “stalker app,” which isn’t wrong! I figured that any location-based app I made would have to explicitly request consent from the user before starting, or give the option to pick a location. But that for another post.)

But polling a server becomes a problem if more people are using an app and too many simultaneous updates emerges as a real concern.

The most accessible solution for web development is websockets, and in a cinch I went with Pusher, which lets you set up a websocket server with a free plan + paid tiers scaling to number of messages a day. Most programming languages/libraries that interface with the internet support TCP or UDP sockets in some form and one can pick based on needs and resources.

Whatever the protocol used, these are low-overhead connections that are kept open between app instances to relay very short segments of data – enough, usually, for you to convey and update positioning, URL pointers, and text content, or to signal for an app to refresh.

Pretty cool! But beyond the technicalities, we also need to think about how to show users that this open connection exists. The easiest and perhaps most obvious is real-time visual updates. A user adds something to the page, that thing shows up on everyone’s page.

But what happens for a user who’s using the app alone?

That seems little outside of one’s control, but there actually is a way to telegraph synchronicity even then: by letting past concurrent users record their synchronous interactions in a clear, textual way.

From the first board in Experiment 3.

This is where the persistence of communicative features is paramount: if a user sees something pop up, they can react immediately with text or an image, and said reaction is preserved on the canvas. This demonstrates to fellow users, present and future, that the interaction happened as a back and forth!

Future users may not necessarily come to this conclusion from seeing past interactions, but it certainly doesn’t hurt to support it.

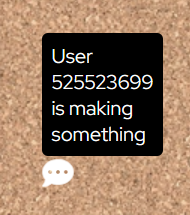

Finally, there are more explicit ways to show that there are other people around, from user icons in a corner, to a “N users online” slug, to . These are often collectively called presence indicators in corporate speak.

I like to employ spatialised presence indicators (like cursors that show “where” other users’ cursors are), but implementing realtime cursor indicators can be heavy on the TCP/UDP server, so since I am lacking a budget, I settle for an indicator that updates when the user makes a significant interaction (e.g. clicking the canvas to open a form).

As with everything else, this requires buy-in from the users. They need to want to play with it! There are ways to invite play, and that could be the subject of another post. But set up the platform right, and you’re at least delivering an open invitation for such interactions.

That’s all for today – thanks for reading! I’m excited to delve into each of the experiments in more detail next.

Leave a Reply